On July 11, 1913, Margery Barber shipped out for Quebec aboard the Empress of Ireland. The passenger manifest listed Canada as her “country of intended future permanent residence”. The socialite wife of her uncle Benjamin had remarked that “when an unmarried young woman gets to 25, I’ve often noticed she begins to call old maids bachelor girls.” Margery was 25 and showed no sign of settling down to breed. If her family’s prayers were answered, she would soon be making herself useful and finding happiness, perhaps even a suitable husband, in the colonies.

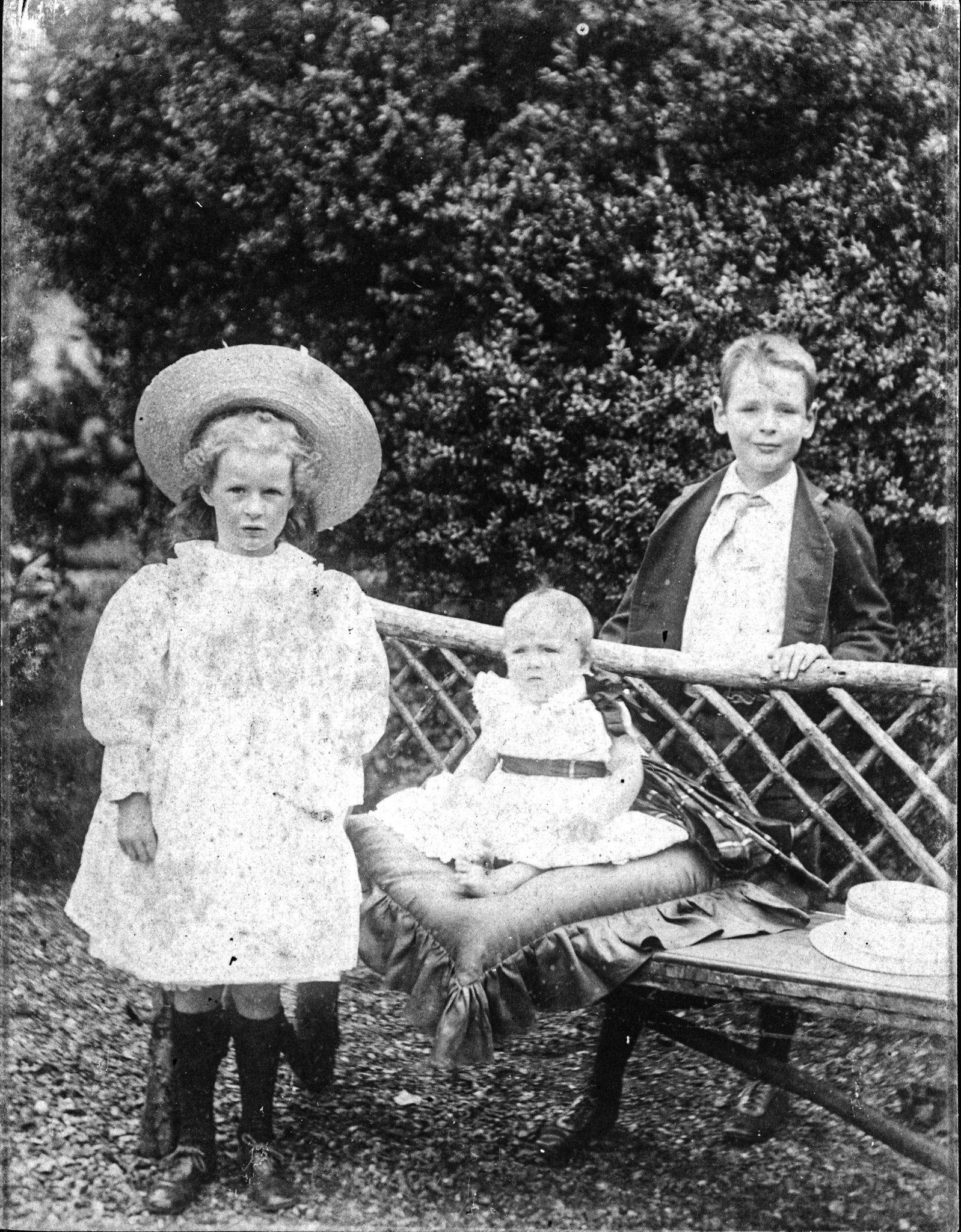

“She had a noble, arresting and charming face and could have married anyone she chose,” her cousin Audrey would recall half a century on. No one else would do the choosing. That was clear to everyone. Whether chasing hares with a pack of beagles, scaling an Alp or wielding a hockey stick, she was formidable. “People were afraid of her,” Audrey said, “She was very strong and powerful.” As a child she was a handful. Today they might have diagnosed ADHD and put her on Adderall. Getting her hat on for church could require the concerted efforts of a governess, a housemaid and the one aunt who had what it took to tame her. Obviously clever — she had an aptitude for languages, becoming fluent in German at finishing school in Weisbaden — she was hard to educate. Teachers, she said, were “my enemy”. Authority tested her patience. The feeling was often mutual. Margery was a rebel, her cause whatever underdog same her way. She would bring home strays, human as well as canine, no matter how ragged or reeking. There were scenes, mostly with Mith, which is what she called her loving but exasperated mother.

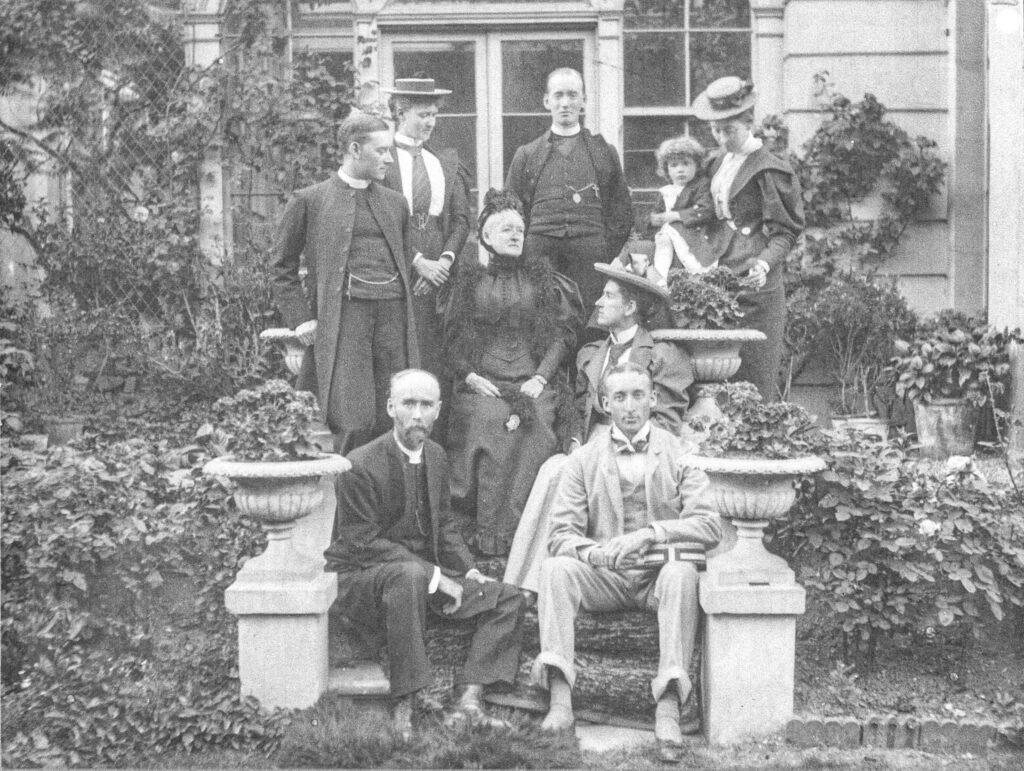

Mith, née Adeline Guinness, exchanged vows with the Reverend Robert Barber on July 30, 1884, at St Saviour’s Church, Pimlico, up the street from 87 St. George’s Square, the London address to which Adeline’s father, Richard Seymour Guinness, had moved his three daughters and six sons (with a seventh in the offing) from Dublin ten years earlier. The couple received 154 gifts, the Bury and Norwich Post reported. Richard, who was busy growing the family bank, Guinness Mahon, beyond its Irish base, and who at his death in 1915 would leave an estate valued at £454 219 14s. 3d. — $75 million in today’s money — gave a piano. Sir Samuel and Lady Ferguson (he a politician and poet rated by Yeats among Ireland’s literary giants, she a Guinness aunt), contributed a “large salver”. Lord Ardilaun from the brewing side of the Guinness tribe was good for a necklace. From below stairs at 87 St Georges Square came a lamp, from “servants in Ireland”, a purse.

Rev. Robert was the eldest surviving child of Rev. Richard, vicar of Riseley, who in turn was the first child of Rev. William, vicar of Duffield and Muggington. Of Robert’s six younger siblings, two of the three boys, Henry and Edward, were also ordained. The third, Frederick, joined the Oxford Mission to Calcutta as a lay brother. Henry, the aforementioned Audrey’s father, had been a chaplain in Biarritz and Cairo, played soccer for several forbears of today’s professional sides, and was a hit at parties for his comic turns, but also, it was said, a kleptomaniac prone to trousering his hosts’ bibelots. Frederick landed a job with Hoare, Miller and Co., a prominent engineering firm, which sent him to India. In Calcutta he moved between the very high and the very low. In 1891, the Viceroy invited him to a ball to meet the future Tsar Nicholas II. His work with the poor destroyed his health.

Robert was a keen gardener. His sweet peas, cauliflower, cabbage and rhubarb won prizes at the Chippenham and Snailwell Horticultural Society annual fête. He collected butterflies and moths, sketched and could give a serviceable lecture on astronomy. Audrey remembered him as “an austere scholar who used to knock loudly on people’s bedroom doors to get them up for church.” He wrote a children’s guide to the catechism, a history of Chippenham from pre-Roman times and a life of Abbot Samson of Bury St. Edmunds, a 12th century divine, in the meter of Longfellow’s Hiawatha. In his preface to the 800-line poem, Robert thanked Lord Iveagh, another Guinness beer baron and one of the richest men in England, for his “generous patronage”.

He also kept a scrapbook of his daughter’s adventures beginning with her departure for Canada. In it, he transcribed Margery’s letters home, adding commentary and illustrations of his own and pasting in newspaper clips and other items for context. The three volumes he filled before his death in 1928 were known in the family as the Margery Book. They are the primary source for the first half of this story.

Adeline left fewer traces than her husband and brothers. That was often the way with Guinness women of her generation. The men went from the best schools into the family racket, acquired titles and stately homes, and worried about their daughters getting hitched to gold-diggers. Adeline’s niece Lucy fell in love with a starving Hungarian artist at finishing school in Munich. They were kept apart for seven years. Only when he began receiving commissions from European royalty was he finally allowed into the clan. The cloth, on the other hand, got a pass. If Guinness girls couldn’t land rich boys, vicars were an acceptable alternative. And, to be fair, there was more to the dynasty than the pursuit of wealth and status. It had a missionary wing — the Grattan Guinnesses — along with a strong tradition of philanthropy and deep ties to the Anglican Church of Ireland. There is no reason to suppose Adeline felt she might have done better when she married Robert even if her ambitions for him may have been a little more expansive than his own. She might pass through the eye of the needle more easily than her brothers, but she did not want for comfort. The census taker who called on the Robert’s rectory in 1911 found a butler, a cook, and three types of maid, lady’s, house and kitchen.

Uncles, aunts and cousins offered Margery and the two brothers born on either side of her highways to God, the establishment and mammon. “I remember Uncle Bob with delight when we watched the procession from the Ritz when ‘Mr. Guelph’ as he called him was crowned, or buried, I forget which,” Margery would write. Uncle Bob was Robert Darley Guinness, Adeline’s eldest brother, High Sheriff of Warwickshire, proprietor of Wootton Hall and squire of Wootton Wawen. Mr. Guelph was Queen Victoria’s eldest son Bertie, Edward VII. The Ritz was the Ritz. Uncle Gerald’s stately pile was Dorton House, a Jacobean gem surrounded by Rothschilds in the Vale of Aylesbury. Uncle Eustace’s seat was Green Norton Hall near Towcester. Uncle Richard entertained Rudolf Valentino and Artur Rubinstein at his place on Great Portman Square. Uncle Benjamin’s addresses included Washington Square in New York and Carlton House Terrace in London. He sat on the boards of the New York Trust Company, Lackawanna Steel Company, Kansas City Southern Railway, Seaboard Air Lines, Duquesne Light Company and the United Railroads of San Francisco. At outbreak of World War I, he saved the German bank Henry Schroder and Co., of which he was then senior partner, from seizure by the British government. As the guns of August 1914 begin to growl, he hurried Baron Bruno Schroder, the bank’s chairman, down to Whitehall. Within half an hour, the right strings pulled, Schroder, who owed his title to the Kaiser, emerged as a British subject.

When Queen Victoria died, Clement, the youngest of the Barber brood, was a chorister at St. George’s, Windsor, the Chapel Royal. He sang at Mr Guelph’s coronation. It earned him a medal for which he would be ragged as a young subaltern in the Royal Fusiliers. “What did you get that medal for, Barber?” “Singing in the choir, sir!” He had come home from Canada in time for the war after his own stab at emigration. Guinness relations had offered him a position in Vancouver where they were investing in vast tracts of land while lubricating the locals with their stout. He found playing the piano in lumber camp bordellos more congenial than getting rich as a member of the family firm, and came home, his boat crossing paths with Margery’s. Invalided out of the army in 1915, he was hired to run a cotton gin in Egypt where he stayed for the next 37 years, racking up three marriages (the first of which produced my father but ended when he was caught in bed with his sister-in-law) and a second medal, designating him an officer of the Order of the British Empire for “services to the cotton buying commissions in Egypt”.

Arthur Vavasour, the eldest, went through the doors that were opened for him and became a banker in London. His youth had passed before the Somme could claim it. He divorced a general’s daughter after she gave him Lavender Jane and Jasmine. Their mother was lady-in-waiting to the Duke and Duchess of Windsor when they were tidied away to the Bahamas for the duration of World War II. Jasmine stayed on to midwife the babies of Nassau’s poor. By that time, Artie, as his sister called him, had run off with the daughter of Stalin’s family doctor. Ekaterina Georgievna Speransky wrote crime novels under the nom de plume Kay Lynn and absconded with the family silver, or so it was said, when Arthur died in 1957. By then he was an object of pity and reproach with a reputation for having been not entirely trustworthy with other people’s money, including his sister’s.

Which brings us back to Margery. She is heading to Vernon in the Okanagan Valley, a garden spot some 200 miles east of Vancouver where the Colonial Intelligence League for Educated Women has acquired 15 acres for “a farm settlement…to enable women of outdoor tastes and training to gain experience of local conditions.”